Volunteering Can Change your Life

SYNOPSIS: The little branch library at Craghaven is one of the last remaining non-computerised libraries in the Western World. When one of its volunteers is found dead on duty in suspicious circumstances, her colleague follows the trail to the local Men’s Shed and beyond.

The first thing out of place I noticed when I arrived at the library to start my shift was the front door was shut. Smudgy glass bounced my reflection back at me. Usually we have the door chocked open, in a welcoming manner, unless it’s an uncomfortably hot or cold day, when we put the air-conditioning on.

Swinging the door open and stepping onto the worn carpet, I could see ahead that the returned books trolley was askew, interrupting my line of sight to the loans desk. A few books had fallen from it onto the floor.

‘Hello, Serena?’ I called, while creeping past the rows of metal shelves in the 600s, packed with chunky gardening and cookery books.

She was lying on the floor. I rushed to her, hoping she had just fainted or fallen, yet already realising it was more serious. I felt for a pulse and couldn’t find one. Her eyes were closed, the brows caught in a frown. Her teeth were gritted together as if she was trying to conquer a challenge or was burdened by the weight of troubled dreams. On her neck, I could see the tiny bitemarks of an imprint similar to a chain necklace or ligature, but nothing like that was visible anywhere nearby on the ground.

Emergency. Get the police. The words zapped through the static in my brain.

I rang triple 0, three quick jabs on the button of the desk phone, and my voice seemed to reverberate around the rectangular vault of a room after I put the receiver down. I’d requested an ambulance even though Serena definitely looked dead to me. All the developments in medicine, I thought, they might be able to revive her. My patchwork tote bag tugged at my shoulder and I eased it onto the chair behind the desk, noticing Serena’s leather handbag on the floor. The clasp was closed, undisturbed. Nothing appeared obviously out of place around the loans desk, as my attention flitted from spot to spot and I tried to observe more slowly and precisely.

I checked Serena again, no suggestion of life. But her body was generating its own pressure in the room, rendering it stifling, and I had to get out. I blundered through the door and concentrated on breathing for a few minutes. This cannot be happening. It’s just a normal day.

My VW Golf hatchback was the only car in the small parking lot, and the community hall to which the library was attached was locked and darkened. I was still staring at its dull windows, struggling to absorb what I’d seen, when the sound of a siren broke my trance and an ambulance pulled into the parking lot. I propped open the front door of the library for the paramedics and pointed in the direction of the body, not wanting to get in the way.

The police arrived soon after: Senior Constable Nick Karakis and his younger colleague, Constable Tahnee Ferris. I gave them my proper name, Adeline, as Addy seemed too casual for the situation. ‘Everything is exactly how it was when I got here. I rang almost straight away,’ I said.

‘Did you see anyone leaving as you approached the premises?’ asked Senior Constable Karakis.

‘No one.’

The police joined the paramedics, making the snug space feel crowded, and I hung back near the entrance. Senior Constable Karakis talked to the paramedics and I heard the word ‘strangled’. Constable Ferris wandered over to me and nodded towards the undersized sofa in Kids’ Corner. ‘Why don’t we sit down?’ she suggested, ‘And you can tell me about the deceased, when she started working here, that sort of thing.’

I explained that we were all volunteers, except for the coordinator, Ingrid de Groen, who was in a paid position, if they needed to speak to her. ‘I trained Serena and then she started doing her own shifts. She’s been here since early this year, around nine months I guess.’ It seemed odd talking about the fallen figure on the carpet; I wanted her to get up and answer for herself.

Constable Ferris’ voice cut in: ‘Do you know of any fears she held, any threats received?’

‘Gosh, let me think.’ I stared at a Wiggles poster on the wall, bright and optimistic, to channel my memory. ‘Not that she mentioned.’

When the paramedics left, unable to perform miracles, Senior Constable Karakis asked if money was kept on the premises, as though robbery might be a motive. I showed him the lower drawer behind the loans desk where a small amount of petty cash was stored in a tin box for incidentals. ‘We don’t bother charging late fees, so there’s no need for a cash register.’ Pointing to Serena’s handbag on the floor, I added, ‘A robber would’ve gone through her bag, wouldn’t they?’

Senior Constable Karakis checked, finding a wallet with ample cash and credit cards. He continued to scan the area and eyed the unsettled book trolley. Most of the returned titles were crime fiction, the staple diet of the locals, who lived in such a quiet and safe neighbourhood they needed an escape. ‘Maybe she tried to use the trolley as a shield to fend off an attacker,’ he remarked.

The blur of a customer appeared at the entrance, cautious yet hovering. Senior Constable Karakis asked me to lock the door and told his junior officer to ‘roll out some tape’. I went to explain to the customer, a young mother with a pink-clad toddler, that we were shut. ‘I’m sorry, there’s been an emergency. Unforeseen circumstances,’ I apologised in a hushed voice and latched the door.

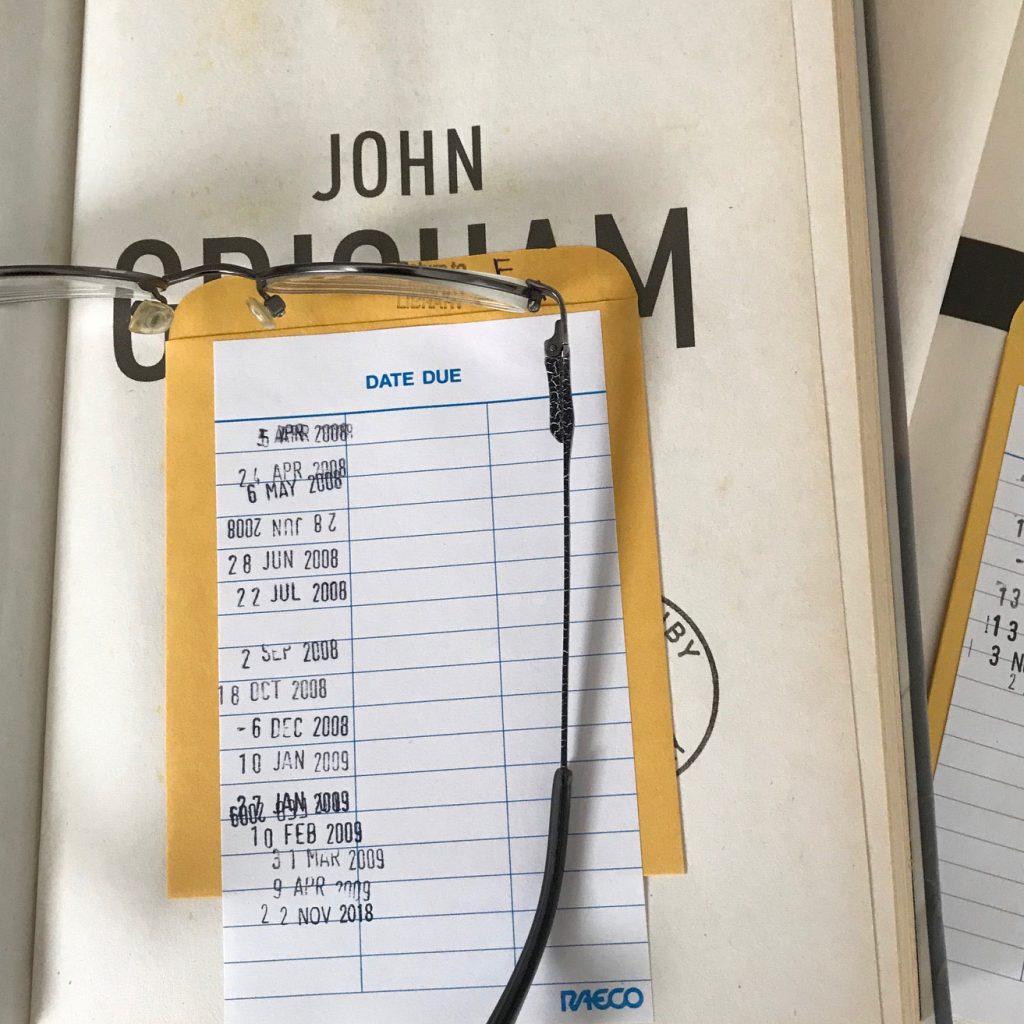

Heading back to the loans desk, I veered wide of the body and kept my eyes elevated. Constable Ferris returned and gazed mystified at the typewriter, the wooden trays of cards, the rubber date stamp and ink pad. The little branch library at Craghaven was surely one of the last in Australia, if not the Western world, to be computerised. It still used a card system: orange for the books, yellow for the borrowers. A hard copy catalogue was housed in a compact nest of drawers, with books indexed by author’s name and title.

The council had advised us that it could not afford the resources to catalogue the books electronically or to link the library to the main network. So we persevered in old-fashioned mode, as closing the facility would be a major blow to the morale of elderly residents who relied on it for intellectual stimulation and social contact.

‘I didn’t know anyone still used typewriters,’ said Constable Ferris, her sky-blue eyes lingering on the giant, metal IBM beast that labelled the cards with the details of the book or the borrower.

I explained about the card system and she blinked at the unfamiliar concepts. She looked to be in her twenties, early thirties at most. I opened the cover of a book sitting on the desk and showed her the due date that was stamped on the pocket glued to the front page. ‘Do you remember before computers?’

She flashed her radiant eyes at me, perplexed and possibly offended, so I added: ‘That’s meant to be a compliment because you look so young.’

A clunking thud, like a fist slamming a hard surface, startled me until I realised it was a book bundling through the after-hours slot next to the door. Some determined customer must have reached past the police tape.

The forensics officers rapped on the glass, wearing heavy duty, dark blue outfits and carrying a camera and a mini padded suitcase which contained brushes and powders. They discussed with the police the problem of too many overlapping fingerprints on the book trolley and the edge of the loans desk. I confirmed that we had scores of borrowers, volunteers and visitors.

I had to stay behind to secure the premises when the police were finished, and I arrived home expecting to fall in a heap, but instead felt strangely energised.

Do you know of any fears…any threats? Constable Ferris had asked. I thought back over everything Serena had told me in the shifts we shared while I trained her.

Migrating years earlier from Malaysia with her husband, Serena worked as a financial planner for a bank, but had been trying to start a family without success and was taking time off to recover from the ordeal. I didn’t want to pry into whether she’d lost a baby or endured IVF, and all I’d managed to ask was, ‘Are you getting some counselling or support?’

She had buoyantly responded: ‘Yes, and it does help, but I find the best thing is to keep busy. That’s why I volunteered here.’

Serena was one of the library’s youngest volunteers, still in her thirties. Most of us are retired or homemakers whose children have grown up. I’m divorced, no kids, and initially after the separation I clung to my career. But slowly I realised that my whole life needed recalibrating. The corporate takeover of my employer, a legal publisher, had prompted a restructure, and five editors in my section were expected to compete for three positions. I was nearing retirement anyway, so I opted to take a redundancy package instead.

Serena told me her husband, Henry, was the head of an IT department and worked long hours. She was worried about his stress levels because he had difficulty switching off at home and kept checking messages from work. With my fanciful imagination, I wondered if he’d been having an affair with a colleague and killed Serena to get her out of the way. Not that I’d met him, but it seems like the husband is often the culprit.

Thinking of marital infidelity, I absentmindedly got out two plates for dinner, which I haven’t done for quite a while. I knew the searing sting of betrayal, the flimsy excuses that are obvious in hindsight, the self-delusion of wanting to believe your spouse. I had suppressed my instincts back then, so I decided to do some delving on Serena’s behalf. What did I have to lose? At most, a bit of pride if I was wrong.

While I was dissecting my chop, the men’s shed at Middlebridge popped into my head. It had come up in conversation with Serena when I was explaining the different processes at the loans desk. Showing her the typewriter, I pointed out that it stalled on the ‘w’ key and you had to hit it two or three times to register the letter. I joked that maybe we should take it to the men’s shed. ‘They have a repair service where you can bring in appliances that need fixing, broken furniture, even knives for sharpening, and they only ask for a donation, a few dollars depending on the job.’

‘That’s handy to know,’ she said. ‘I’ll keep it in mind. There’s too much wastage nowadays.’

Then a week ago, when we had a quick chat at the changeover of our shifts, Serena mentioned that she had taken an item to the men’s shed for repair. I soon forgot exactly what it was – a board of some sort. Drainage board, chopping board, white board? But I did recall her saying it was funny to see a gathering of old men playing with tools and equipment, whereas in Malaysia, groups of old men play mah-jong or chess.

I convinced myself to visit the men’s shed, on the off-chance that anyone remembered Serena. The disturbing notion that nagged me was that a psycho working there might have developed an infatuation with Serena, who was quite pretty, and killed her. If that was the case, I would feel terribly responsible for recommending the repair service to her.

I went there after my library shift the next day, armed with a picture of Serena on my mobile phone, taken from the passport photo she had supplied for her volunteer registration form.

The men’s shed was in the former hall of the Second Middlebridge Scout troop, which had been disbanded as surplus to requirements of the ageing suburb. Inside was a cluttered space of work benches topped with machines like sanders, grinders and lathes and, around the walls, metal lockers, storage shelves and tools hanging from hooks. Smells came to me from years ago – linseed oil, construction glue and machine oil – conjuring my ex-husband tinkering in his workshop.

A tall, thin man approached, with a heavily lined face and a crop of greying hair that was thick for a senior male.

‘Hi, I’m Addy,’ I said. ‘I work at Craghaven library. I don’t think I’ve met you before.’

‘I’m Ross.’

I explained that I was a colleague of Serena’s and she had mentioned getting something repaired at the shed; I was trying to help the police by collecting information from anyone who had spoken to her recently.

‘Yes, I heard about it on the wireless. Terrible business,’ said Ross. A glow of readiness to help burned in his eyes, and I found it difficult to picture him as a murderer.

I showed him the photo of Serena on my phone, apologising that it wasn’t the best quality. He didn’t recognise her, but looked for her name in a red log book of jobs.

‘It would be within the last couple of weeks,’ I prompted.

Eyebrows twisting over his whisky-brown irises, Ross scanned the entries. ‘There it is,’ he pointed with a bruised fingernail. ‘Broken drawing board. I’ll just check if any of the blokes here were involved. Can I show them the photo?’

I handed him my phone and watched him go to speak to a group of men clustered around a work bench. Ross returned with a short, balding man called Clive. ‘Yes, I remember her bringing it in,’ he said. ‘She was polite, pleasant, not like the young lass who kicked up a fuss later.’

‘When was this?’ I asked.

‘Let me think now. I’m here two days a week and the first lady came in on Tuesday. So it must’ve been Thursday when the younger one turned up, quite stroppy.’ Clive was slightly more conceivable as a murderer, I thought, blinking and nodding as he concentrated on getting his facts straight. ‘She said the board was hers and she didn’t want it repaired.’

‘Did she say how she was connected to Serena?’

‘No. I assumed a relative of some sort. Her daughter?’ suggested Clive.

I shook my head. ‘She doesn’t have children.’

‘What sticks in my mind is her saying, “Don’t bother with it because Dad’s going to buy me a new one.” But it was too late, we’d already started fixing the contraption.’

‘What did she look like?’

‘Same background as the other lady – Asian,’ said Clive. ‘Late teens. Her hair was dyed a bright colour. Green or blue, or maybe purple. Colours aren’t my strong point.’

‘So did she take the board away?’

‘She said her father would come to pick it up, but it’s still here.’

‘Can I see it?’

Clive and Ross ushered me over to an area of completed jobs. A director’s chair, an ‘Ab Cruncher’ machine and a child’s tricycle were parked on the floor in front of metal shelves packed with smaller items including a stereo, a mantelpiece clock, even a pair of work boots. The drawing board consisted of a base and a tilted melamine plank with a parallel rule and knobs for adjusting the angle. Something that an architect or artist would use for drafting, about the size of a primary school desk-top.

I thought the police might wish to talk to Clive while he was at the men’s shed, so I rang the station but Tahnee Ferris wasn’t available and neither was Nick Karakis. I left a message for Tahnee and took down Clive’s full name and contact details.

By the time Tahnee called me back I was at home. I told her the story and pointed out that Serena didn’t have a daughter. Tahnee said she’d pass the information onto the detectives, who could ask Serena’s husband.

A couple of days later I checked with the men’s shed and the drawing board still hadn’t been picked up. I realised it might be a good opportunity to manoeuvre myself a little more into the family circle, in the quest to trace the antagonistic young woman.

I rang Serena’s home number to see who answered, fingers trembling as I tapped the digits. It was a man’s voice, presumably her husband.

‘Hello, is that Henry? I’m a friend of Serena’s from Craghaven library. Adeline. Please accept my condolences. I’m very sorry to disturb you at this time.’

‘That is all right. Many people are ringing.’

I explained about the drawing board and offered to drop it back to wherever it belonged. ‘Here will be fine,’ he said and we made an appointment for late that afternoon. I figured he was on leave from work, as would be expected when someone is grieving and making arrangements on behalf of their family.

* * *

The house was a toffee-painted cottage with a steeply gabled roof, reminding me of a gingerbread house. It was an overcast day and the hallway light came on when I knocked, glowing through the glass inset in the door.

‘Hi, I’m Adeline, with the drawing board.’ I hoisted it higher on my hip.

‘Please, come in.’ Dressed in a V-necked vest over a collared shirt, trousers and house moccasins, Henry took a few shuffling steps backwards into the lobby. He stopped at a hall table where a Ming-style vase stood, shifting it to make room to rest the drawing board.

‘It’s all fixed,’ I said, keeping a steady hand on the board.

‘That is very kind. My niece will be glad. I hope you didn’t go to too much trouble.’

‘It’s the least I can do.’

I admired a gallery of family photos on the wall next to us, extending up the hall.

‘There she is,’ said Henry, pointing to a group photo of a young man’s graduation, finger zeroing in on a girl with blue streaks in her hair.

‘What’s her name?’

‘Lily.’

‘Is she studying architecture or design or something?’

‘Fashion design, I think. It’s hard to keep up with young people.’ His voice was monotone, like a recording of a simulated voice, although perhaps that was melancholy.

‘She looks very creative.’

‘Yes, she’s the artist in the family. She’s in charge of making the photo tribute of my wife for the service.’

‘So she got on well with Serena?’ I ventured.

‘Why wouldn’t she?’ Henry stiffened. ‘At least, as well as can be expected when people are from different generations.’

‘Of course,’ I said.

He passed a hand over his forehead. ‘Excuse me, I am not in a very talkative mood.’

‘I understand. I didn’t mean to intrude.’

I sat in my car, trying to decide whether to go to the police. All I had was a suspicion of some kind of minor disagreement between Serena and her niece. It sounded weak, although the police always say in those public appeals on television that the smallest detail, no matter how insignificant it seems, may be relevant.

I had just resolved to drive to the police station when a flash of colour bolted from the bushes and up to my car. A figure yanked open the front passenger door and plonked into the seat, clutching a phone. It was Lily, the young woman with blue-streaked hair in the photo. I must have resembled a stunned mullet, no time to mask my surprise.

‘Who are you?’ she demanded.

‘I could ask you the same thing.’

‘I asked you first.’

‘I worked with Serena at the library,’ I said. ‘Were you hiding in the bushes?’

‘No, I was coming to visit my uncle when I saw you go in the front door with my drawing board, and I want to know why you’ve got it.’

‘I was bringing it back from the men’s shed where they repaired it, good as new.’ While I spoke, I tried to keep thinking in a separate compartment of my brain. Is this girl dangerous? Is she going to turn on me?

Lily asked a question of her own: ‘Can you drive me to the police station?’ A sapphire stud glinted on the side of her nose.

‘The police, why?’ If she’s a killer, she wouldn’t want to go near the police.

‘To tell them about this guy I know who’s acting psycho. I’m worried. I was going to talk to my uncle but it mightn’t be such a good idea, he might think I’m mixed up in what happened to Aunty Serena,’ she rambled.

‘Is he a friend of yours, this guy?’

‘Sort of. He’s not officially my boyfriend but, like, when I come home for the holidays we hook up and then when I’m down in Melbourne I decide to stop seeing him.’

‘And what could he have done?’ I asked.

Lily tossed her blue streaks, shutting me out. ‘I don’t know, I’ve just got a bad feeling.’

During the drive, she kept her head bowed, her attention fixed on her phone.

In the waiting area at the police station, I tried to sound as though I was making casual conversation rather than snooping. ‘So, what takes you to Melbourne? Studying?’

Lily glanced up from scrolling and nodded. ‘Fashion design at the Millbank School. It’s a very prestigious course. My plan is to be a stylist.’

‘A hair stylist?’

‘No, it’s designing the whole look of the person. Sort of their image, their brand.’

I wondered who on earth would employ someone to do that, but avoided saying anything negative.

She eyed me curiously, twisting her head. ‘So you worked with my aunty?’

‘Yes, she was lovely.’

‘Everyone says that. I gave her a hard time, I guess. It’s just that she was always in Mum’s ear about me.’

‘In what way?’

‘Aunty Serena was the big finance expert in the family because of her job, so Mum and Dad listened to her. She stopped them buying me a car. But I wouldn’t wish her any harm. I didn’t do anything.’ She shone her glittery eyes at me, thick with eyeliner and mascara.

‘But you’re worried this fellow might have done something? What’s his name?’

‘Josh. He gets intense. It’s scary.’

I hoped Lily was going to reveal more, but at that moment the desk sergeant signalled her to come forward. As she stood up I said, ‘Do you want me to wait around, give you a lift somewhere?’

‘That’d be cool,’ she nodded.

I read the posters on the noticeboard for missing persons, who at least had a chance of being found alive. Serena was dead, which still didn’t seem real, and I wondered what she would think of me befriending members of her extended family.

When Lily came out I asked, ‘How did it go?’

She said she’d seen a blonde lady, but didn’t catch her name.

‘In uniform? Bright blue eyes?’

Yes and yes. Presumably Tahnee.

Lily talked fast, buzzing. ‘I told her how my aunty was trying to stop me staying in Melbourne once I finish the course, because of the money. She was obsessed with me getting a regular job. As if I’d want to be like her and work in a bank. Bor-ing. Josh blew up when he found out and said he could give her a scare. I said no, and now he’s disappeared and my aunty’s dead. I’ve texted him but he hasn’t replied.’

‘Sorry, I don’t understand why Josh would want you to stay in Melbourne if it means being apart?’

‘He was going to move down there with me. Get a flat or share a house. He was kind of pinning his hopes on it, to shake off some people who are hassling him. Check out the art scene. He does street murals. But it depends on me getting the money.’

Young man. Hothead. Financial pressures. It sounded like a potent combination. I’d read articles that said young men often behave recklessly because their brains are still developing.

* * *

Serena’s funeral was held in a chapel at the Northern Suburbs Crematorium, with its Spanish mission architecture and mazes of paths around gravel rose beds. It was a drizzling day of intermittent showers, umbrella up, umbrella down. I arrived early and waited under a dripping tree. Tahnee attended in civilian clothes, admitting her strategy was to see if Josh the boyfriend turned up.

‘Malaysians, are they Buddhists?’ I wondered aloud.

‘Not sure. I didn’t get any religious vibe when we interviewed the family,’ Tahnee replied.

Sure enough, the woman officiating at the service was a celebrant from a local funeral provider, not a religious representative. When we filed into the chapel, an attendant handed us each a program and Serena’s face stared wistfully from the cover. The family sat up the front of the chapel and Lily’s blue hair stuck out. The coffin was shrouded in white roses and the smell of incense floated on the air. Given Lily’s dramatic personality, the photo tribute was more conventional than I expected. Serena transformed in a series of portraits, from a cute baby to poised professional, while “My Heart Will Go On” played and my vision dissolved into a salty mist.

At the end of the service, the celebrant announced: ‘The family extends a very warm welcome to all of Serena’s friends to join them for afternoon tea.’ In the printed program, the address given was 26 Odelia Drive, not Henry and Serena’s residence.

The address turned out to be where Lily’s family lived, in a nouveau-Federation house with orange bricks, imitation leadlight windows, spindly wooden lightning rods and spotless roof tiles. The wide driveway was bordered by small trees in tubs and a thicket of folded umbrellas sprouted near the door.

Tahnee introduced me to Serena’s sister, Angelica, who welcomed the guests. She looked like an older, shorter version of Serena and smiled warmly, sandwiching my hand between her two palms for a suspended moment.

I wandered through multiple living rooms, past a glossy upright piano and French provincial-style furniture to a rear terrace where most of the mourners were gathered under a pergola. There were people from the Malaysian community and suited, corporate types who I presumed were colleagues from the banking world. Cups of tea, soft drinks and mineral water were on offer, no alcohol, unlike at the funerals of elderly Anglo-Celtic neighbours I’ve attended, where everyone rushes for a glass of wine to relieve the nervous fear that they might be next.

I needed to go to the toilet and was shutting myself in the powder room when Lily dashed past, staring at her phone as though summoned by a message. Quick as I tried to be with my ablutions, she had disappeared when I emerged. I followed the direction in which she’d gone, towards the front of the house.

Through the panelled windows, I saw an ungainly duo of interlocked bodies, stumbling across the yard. I spun on my heel, calling for Tahnee, and scanned the terrace but couldn’t spot her blonde head. There was no time, I didn’t want to lose contact with Lily. I imagined Josh might have lured her outside and grabbed her.

I clattered out the screen door, as a motor gunned and tyres squealed on the wet road. Running up the driveway, I noticed a trail of red splotches. Were they blood? If they’d been there when I arrived, I hadn’t registered them. My car was parked a few metres in the opposite direction and I ran to it through the spitting rain, forgetting my umbrella in the panic.

Ignoring the ‘local traffic’ speed limit, I found myself gaining on the car that had fled. The Toyota Corolla sedan didn’t look like a young person’s car, and I thought perhaps Josh stole the keys from among the bags that the guests had left in the front sitting room, if he’d snuck in when no one was paying attention. I couldn’t see who was driving, but the bobbing figures gave the impression of struggling or interference.

A bend in the road loomed and I slackened off, hands still fused to the steering wheel as the windscreen wipers squeaked. No chance to stop and call Tahnee.

Pushing my luck, banishing doubt, I remembered what I pledged during my divorce: I would no longer give into fear. Back then it was the fear of being alone, the fear of starting again. On this mission, my immediate fears were having an accident, losing my nerve, failing to make a difference.

Keep going. Do it for Serena, for the police, for all the dead women.

When I caught sight of them again, on a straighter stretch, the car was veering across the lane, slick in the wet, blotting out the centre lines. It disappeared around another bend.

The sound came before vision, a magnified screech and metallic explosion. I immediately slowed my speed, as if somehow the force of the blast could hit me.

The rear of the Corolla was unscathed but strangely fused onto the front, compressing the middle of the vehicle. The crumpled bonnet embraced a telegraph pole. The driver must have lost control.

I braked ahead of the wreck and ran back, the speckles of rain prickling my skin. The bodies were trapped in the front seats, wedged against the dashboard. In the driver’s seat, Josh looked like a boy, except for the barbed-wire tattoo on his twisted neck.

There were streaks of blood and cuts on both their hands. The blade of a knife glinted from the pushed-up floor. My first instinct was to retreat to a safe distance and call Tahnee, but I realised the seat belts ensnared them.

Lily moaned, ‘He’s not answering me. Is he dead?’

I reached out, touching his shoulder.

Josh’s eyes jerked open a crack.

‘I’m getting help,’ I said, phone in hand.

‘Don’t bother. It’s not worth it,’ he said.

‘Of course it is. Hold on,’ I urged.

‘I can’t,’ he croaked.

‘Please. The family needs to know. The community. We all do.’

A few more puffs of air inflated his lungs, just enough to add: ‘Don’t – believe – Lily. She’s a sicko. She did it.’

© Rowena Helston 2017