The Sound of Your Voice

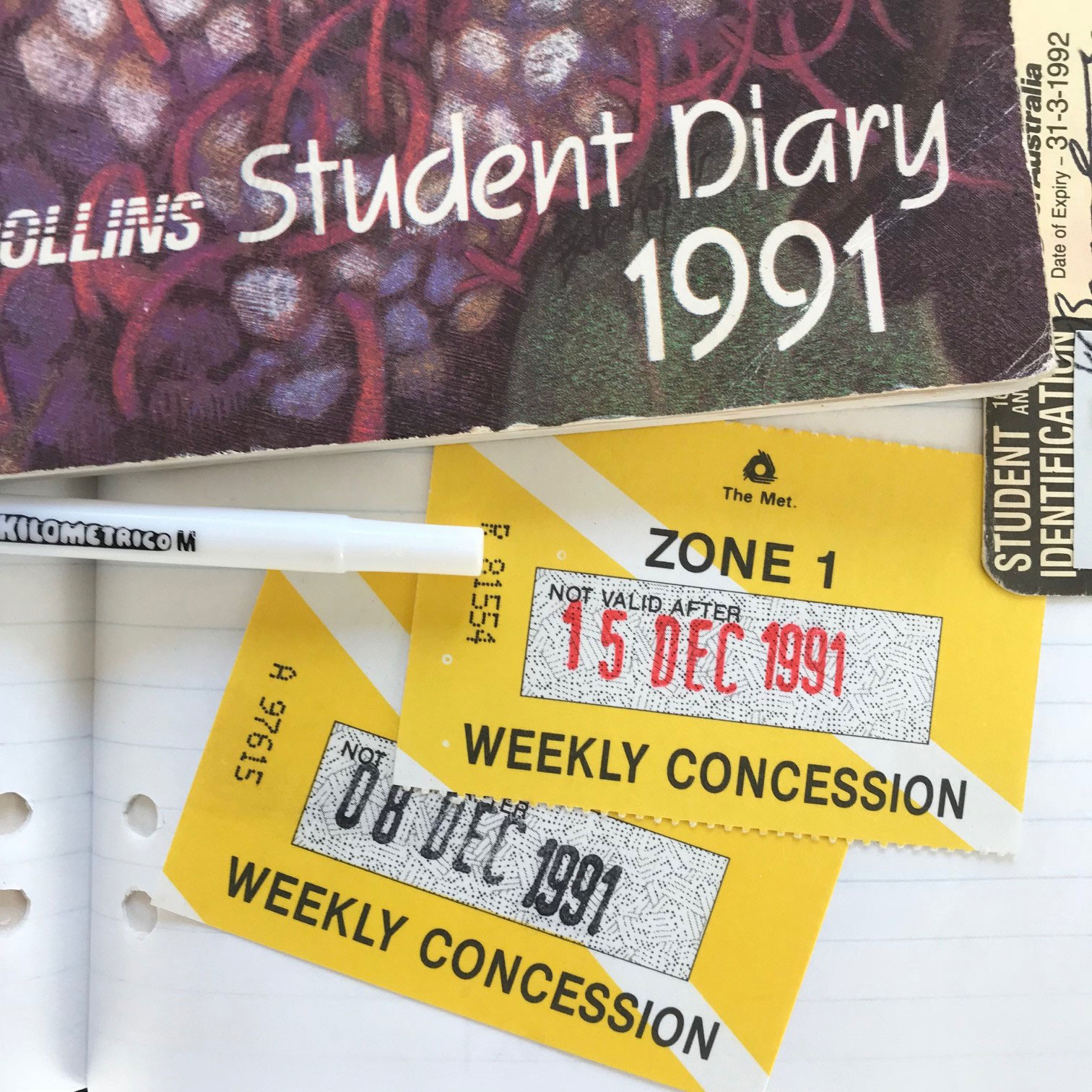

SYNOPSIS: Katrina, a country girl attending university in the early 1990s, goes out for a night in the city with another young woman from the rooming house where they live. As they enter the male world of television and radio stations, Katrina becomes increasingly concerned about her housemate’s obsessed behaviour. This early story became the basis for a novel in which the events lead to murder.

Catching the tram into the city, Tammy keeps looking out the window at the cars going past. She says she’s checking for a red Camira with Tasmanian number plates that belongs to a friend of hers who drives along this way to work.

When we get to town she wants to stop off to ring Kerry, the girl who used to have my room, to tell her to watch out for us in the studio audience. Kerry’s travelling around Australia and is staying in a youth hostel in Sydney.

I consider ringing my parents but they don’t like ‘Late Talk’. Dad says that Danny Stevens prances around like a trained cockatoo, and Mum calls him ‘uncouth’. After finishing my homework, I used to look forward to the night scenes at the start of the credits. The show has an energy about it, a city vibe that I couldn’t wait to experience in person when I was accepted into university.

We catch another tram from the city to the TV studio. Walking down the hill, I button my denim jacket halfway up, as I can feel the temperature dropping.

‘Vet science,’ says Tammy. ‘You must be pretty smart to get into that.’

‘I wouldn’t be so sure. Maybe it’s just because I grew up on a farm,’ I say.

‘What sort of animals are you interested in?’

I tell her I want to work with livestock in the grazing industry.

‘Isn’t that weird? You’ve got to come to the city so you can work in the country.’

Tammy says she used to have a job as a receptionist in a doctor’s surgery but she took a few too many days off. ‘Anyway, it’s a full-time job keeping up with all the TV and radio business in this city,’ she adds.

People are queueing outside the glass doors to Studio C. ‘There they are, all the good people lining up with their tickets,’ she says.

‘Tickets?’ A chill runs through me. She never mentioned tickets before.

‘The general public is supposed to have tickets, but I know some people of importance around here.’

We stand under a scrubby tree while the ticket-holders file inside. Tammy puffs on cigarettes and looks over her shoulder. ‘The guy in the leather jacket. Lex. He’s the audience supervisor, a real bastard. Get your arse inside, Lex, back where you belong.’

She smears out the cigarette with her toe and takes another fast look around. ‘Good. There’s Geoff. The doorman. He’s a really great guy. We’ll go up and see him in a minute when the last of the cattle have gone in.’

Geoff is smiling into space at the top of the steps, shuffling a wad of tickets. ‘Hiya, Geoff,’ says Tammy.

‘Greg.’

‘God, of course. Greg. Sorry, Greg.’

‘You haven’t got tickets, have you?’ he says, but there’s no anger in his face. If anything, the smile is wider, like he enjoys having the power to dispense mercy.

‘Greg, this is my friend Katrina. She’s from the country. She’s a big fan of the show and this is the only night she’s in town, but it was too short notice to get tickets.’

I clench my teeth to keep the shivering under control.

Greg nods at the hot dog seller camped next to the street light on the verge below, for the easy pickings. ‘Buy me a hot dog and you’re in,’ he says.

Turning on a heel, Tammy digs coins out her jeans as she strides down the slope, with me jogging to catch up.

Greg eats the hot dog slowly, running the tip of his tongue around his mouth to collect the residue mustard.

‘Our tickets taste good, do they Greg?’ smirks Tammy.

He waves us in, telling us to stand against the far wall. Everyone else is packed into rows of plastic courtesy chairs. Clipboards move slowly along the rows. ‘They’re the audience questionnaires,’ explains Tammy. ‘So the crew have some victims to hassle in the commercial breaks. Gotta keep the punters amused in a live show.’

I lean against the wall and watch the Danny Stevens fans, decked out in ‘Late Talk’ caps and t-shirts. Lex, the audience supervisor, calls the waiting room to order and gives us a lecture about the show’s format and proceeding to the studio in an orderly manner. When the second row stands, Tammy motions me to follow. I wish desperately that I could walk with my eyes shut.

A girl near us, wearing her ‘Late Talk’ cap backwards bleats, ‘They’re pushing in!’

‘You got a problem?’ scowls Tammy.

‘You’re the one pushing in, bitch.’

‘Go fuck a brick.’

Before she can respond, the girl dissolves into the bright studio light.

Tammy switches back to a smile for me. ‘Don’t worry about her, she’s always bossing everyone around. Thinks she owns the place.’

I nod, and it feels like nodding under water. Everything is under water, with a slow-motion glow.

Sitting in the spongy blue seat in the second row of the studio audience, I keep expecting a spotlight to land on us and the security guards to come and throw us out. But they don’t. Everyone is happy now, leaning forward in their seats as the theme music erupts.

I can’t see much. All the cameras and technicians are in the way. We’re supposed to watch the show on monitors hanging from the ceiling, but I soon get a stiff neck.

The audience coordinator jives in front of us, signalling when to clap and when to stop. Before the show, he told us not to whistle because it zaps the microphones and not to wave if the camera flashes onto us, but screaming is okay. He tells us to scream like crazy when Danny makes his entrance. In the commercial breaks, the audience coordinator throws lollies at us. Not to us, but at us.

Danny’s guests are a racing car driver, an American woman who writes trashy novels that are made into telemovies, and a man who can eat incredibly fast. He says it all started when he won a donut-eating competition at a shopping centre at the age of eight. Danny gives him a tray of food and ties a bib around his neck and we all count aloud to twenty while the man demolishes the lot.

Tammy doesn’t pay much attention to Danny Stevens. She’s more interested in the crew. She says they’re the real talent, especially Duke, the floor manager, a lanky guy who dashes around the set all evening. At the end of the show she worms through the crowd to reach him.

Duke recognises her but can’t remember her name.

‘It’s Tammy. You did an excellent job tonight, Duke.’

‘Thanks.’

‘I find your work really fascinating. Actually, I was wondering if we could talk about your job some time. Maybe have lunch or something.’

‘Sure.’ The smile is stamped onto his face.

‘When would you be available?’ she persists.

‘How about I give you a ring?’ He takes a pen from his shirt pocket and writes down the rooming house number on the back of a schedule sheet.

‘What time roughly would you be ringing?’ she asks.

‘How about Monday? That’s when I get my roster, so I’ll have a better idea of my movements by then.’

‘That’d be great.’

After she’s finished with Duke, Tammy wants to say goodbye to Greg, but the security guard says he’s in the green room and we’re not allowed up there. I tell Tammy to forget about it, that we should get going.

‘Can’t you page him or something and tell him to come down here?’ Tammy says to the guard.

‘No, I’m afraid that’s it for tonight, girls. We’re locking up now.’

Outside, the breeze is picking up. Tammy dances around in it. ‘Isn’t it excellent about Duke? His real name’s Andrew – they call him Duke because he loves John Wayne movies. What if I started going out with him? What about Geoff? I couldn’t go out with both of them.’

‘Greg.’

‘I mean Greg.’

At the tram stop, Tammy reviews the show in detail, as if I wasn’t paying attention. ‘You got a really good shot from Camera Three,’ she says, wagging her cigarette at me. ‘After the second commercial break. The camera flashed right on you – didn’t you see yourself on the monitor? Never mind, I’ll play back the video for you when we get home.’

So my parents could’ve seen me after all. Their little girl in the big city.

But the night isn’t over yet. Tammy wants to drop into ACE FM on the way home, to see a friend of hers.

Eventually I give in. It’s quicker than standing there arguing with her.

Radio station ACE FM is on the top of a skyscraper in Festival Street. Security doors and an intercom are located at street level. Tammy stops at the foot of the steps and pulls a Walkman out of her bag. She twists the ear plugs into her ears, then whips them out again. ‘Perfect, he’s just going to an ad break.’ She’s already bounding up the steps. ‘He’ll play four ads and then the station promo.’ She hits the intercom button.

‘He’s a D.J.?’ I ask.

‘Sure is. Rod Phillips. He usually does the graveyard shift but Scott Bryce is sick, so Rod is filling in for him tonight and Troy Dennis is filling in for Rod.’

Tammy keeps thumping the intercom button but there’s no answer. ‘He’s probably talking to a caller, or maybe he’s in the staff room – he wouldn’t hear the buzzer from there.’

She decides to wait on the steps for him. ‘There’s only fifteen minutes to go before the end of his shift. We can watch from here and stop him when he drives past.’

I put my foot down. ‘Look, no, I really don’t want to hang around. It’s late and getting cold. I think I’ll call it quits for tonight.’

‘It’s only for a couple of minutes. He’ll give us a lift. We’ll end up getting home quicker this way.’

‘I don’t think we should be asking some D.J. for a lift.’

‘He’s a good friend of mine.’

‘What if he doesn’t drive past?’

‘Rod always drives home along Festival Street. The minute he sees me he’ll stop.’

‘What if he’s going too fast to see you?’

‘He’ll get held up at the traffic lights. It’s impossible to get straight through after turning the corner. The lights are rigged that way. Believe me, this is the best place to be. The alley where the carpark comes out is bad news.’

People wander up and down Festival Street and disappear into late night bars and clubs. We sit on the steps, waiting for Rod.

‘Christ Almighty,’ says Tammy and I look up to see a guy in chains being led down the opposite side of the street by a few mates. The guy in chains is wearing a dunce’s hat and the backside has been cut out of his jeans. ‘Not a bad arse, though,’ says Tammy. It looks unnaturally white under the glare of the street lights.

‘How about we get a cab?’ I say. ‘I don’t mind paying.’

‘Rod will be here any minute, I guarantee it. Ain’t there some crazy people around?’

The procession disappears into a bar.

‘What sort of car does he drive, anyway?’ I say.

‘A red Camira.’

A couple of sailors come up to us. They’re so young that if they didn’t have their kit bags, if they were just in uniform, I wouldn’t believe they were real. I’d think they had been to a fancy dress party or got separated from the man in chains.

The sailors are from Geelong and they tell us about patrolling the Pacific. Then suddenly, as if they’ve heard a secret signal, they look at each other, hoist their kit bags, and go.

It’s twenty past one. ‘I’m getting us a cab,’ I announce.

‘Five more minutes, ‘ pleads Tammy. ‘He’s probably just dubbing off some ads.’

‘Five more minutes, then whatever comes first, a cab or – ’

‘Red Camira!’ yells Tammy and leaps off the steps.

She catches Rod at the traffic lights, just like she said. The look on his face is priceless. He pulls over and winds down the passenger window. ‘Tammy. Hi. What are you doing wandering around at this time of night?’

‘Hiya, Rod. This is my friend Katrina. We’ve been to Late Talk.’

I smile apologetically, trying to let him know this wasn’t my idea.

‘We thought we’d drop by to say hello on our way back through town,’ Tammy goes on. ‘But there was no answer on the intercom.’

‘That’s strange,’ says Rod. ‘I didn’t hear anything. Maybe there’s a problem with the intercom. I’ll get them to check it out.’

‘So you were doing your own panelling tonight?’

‘Yep. Up there all on my ownsome. Look, I really shouldn’t double-park like this.’

‘Actually, Rod, I was wondering if you’d be able to give us a lift. Just to Taylor Parade.’

He picks at the leather cover on the steering wheel for a moment and sighs. ‘Okay, hop in.’

Tammy talks all the way, her frizzy hair bobbing over the top of her seat. ‘How’s Annette? Did she get the promotion? Are you going back to your regular shift tomorrow night? Do you remember Kerry, the girl I was with last time you gave me a lift? Well, she’s travelling round Australia and we’re keeping in touch and she said she’s really missing the sound of your voice. So I was wondering – I know it’s asking a big favour – if you could give me one of your audio-dub tapes to send to her.’

Rod’s troubled eyes connect briefly with mine in the rear-vision mirror. ‘That’s an unusual request but I’ll see what I can do,’ he says.

He drops us off at the next cross-street. I start wandering up the footpath while Tammy clings to the open car door, snatching a few more moments with Rod. Eventually I hear the door slam and the car drive away. Tammy catches up to me. ‘Well, what do you think? Isn’t he gorgeous? Rod, Geoff, Duke. What am I going to do?’

I don’t bother correcting her about Greg. I even smile, because we’re nearly home and our rooms have locks on them.

The building from the outside looks like a block of flats, with bricks the colour of rust, but inside it’s divided into single rooms. There’s a shared bathroom on each level, and at the rear is a communal area: kitchen downstairs, TV room upstairs.

Tammy flicks on the entrance light and sets the lobby ablaze. I can smell sausage fat from earlier in the evening, when the cooking fumes would’ve drifted down the corridor from the kitchen.

‘You’ve been a very good girl tonight,’ she says, ‘And I know you’re half asleep, so I won’t play back the show for you now. Get some rest and I’ll come and visit you bright and early in the morning.’

© Rowena Helston 1992